Last month’s Dharma Byte addressed finding the balance in daily life that comes from Zen and its meditation; and the fact that practicing Zen itself requires striking a balance between time devoted to zazen and time demanded of our responsibilities to family, household and career. This dimension of Zen practice may be thought of as developing “social Samadhi” along with the more personal dimensions of Samadhi – physical, mental and emotional levels – that grow stronger over time on the cushion.

Other social examples of balance or imbalance may be witnessed in what passes for justice and reconciliation between individuals, groups, and even whole nations. The Nuremburg trials as well as those of the Japanese military after WWII are examples that stand out in memory for my generation; more starkly for our parents’ generation, who fought that war; and fading quickly into obscurity for our children’s generation. George Santayana’s warning that “Those who cannot remember history are doomed to repeat it” never seemed clearer to me, though I never felt that I could learn much from studying history, personally.

One reason is summed up in another famous quote from Winston Churchill, “History is written by the victors.” History is suspect for a number of reasons. The history of Zen, for example, is incomplete, as is any history. Matsuoka Roshi considered history to be one of the great deceivers in that it creates a distorted impression, for example that only one Zen master, such as Master Dogen, was preeminent during a given period. Nothing could be further from the truth. But it is exceedingly difficult to grasp the bigger picture of interdependent interplay of contingent events, causes and conditions of the times.

The trial of German Nazis for war crimes garnered the greatest amount of attention after the war, and has enjoyed the most retention in public memory as determined by media coverage, especially that of Adolf Eichmann. Trials of the Japanese are not as iconic, though seared into the memory of those Allied forces held as prisoners of war. Something like 5,000 combatants were identified as “war criminals” and sentenced to be punished, ranging from death by hanging to lifetime incarceration. Hundreds of POWs volunteered as hangmen. The lone judge to vote against criminalizing Japan’s wartime behavior was from India. She maintained that the Japanese were pushed into war by actions of the USA.

We saw a willful revisionist history after the Vietnam War, with resultant pain and social distortions still with us today, in the form of PTSD and other disorders. We are witness to perhaps the most grotesque manifestation of war in the unfair competition for needed services between vets of Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. The old saw has it that time heals all wounds, but not if they are not cleansed. They simply fester, and become worse. And it seems that we simply do not know how to clean some kinds of wounds.

Before turning to the personal side of this tragic dimension of life, it is worth noting that the public pronouncements surrounding these events often repeat the same refrain. The issue is presented as a choice between “moving forward” or “looking back.” The former is touted as the positive, progressive and forward-looking option, while the latter is deemed negative and retrogressive. The forward approach is the choice of those who want to “move on,” get on with the business of the future, not get bogged down by “water under the bridge.” Those who want to revisit the past insist that it is not possible to have a fresh start without redressing grievances. It is instructive to note that the former position is predictably taken by the victors, and relative aggressors, to the recent unpleasantness; while the latter position is just as predictably held by the relative victims, the oppressed. Over time, the two sides often switch positions, so that after centuries of internecine conflict, the attempt to determine original sin becomes an endless regress into the dark mists of forgotten history. Forget, Hell! captures this sentiment in the case of the US Civil War. The truth is, we can only move forward by looking back, simultaneously.

A recent special on television recounted the provenance of the Parthenon, the iconic example of Greek architecture gracing the Acropolis of Athens for all these many millennia. The story goes that the rulers of Athens offered up their daughter as a human sacrifice to quell a conflict that threatened the cohesion of the community. It struck me first, as an example of the lost sense of noblesse oblige, the idea that those who most benefit from society should step up to make the most sacrifice in times of crisis. Why the daughter is offered up, rather than the self-sacrifice of one of the principals, is open to debate, of course, along with the sacrifice of Isaac. The details of the story and its accuracy are not important here, but the point made by a commentator, that we do not have human sacrifice today, hit me with a force currently characterized by the colorful expression, gobsmacked.

If we are to learn anything from history, it should be the answer to that line from the song made famous by the late Pete Seeger, Where Have All the Flowers Gone?: “When will we ever learn?” What is the volunteer army if not human sacrifice? The youth of the nation—more accurately the youth of the lower income/opportunity segment of the population—are routinely sacrificed to the professed “vital interests” of the nation in recurrent forays in international adventurism. It becomes obvious that these so-called vital interests reflect those of international corporate entities more than they do any legitimate interests of the body politic of the USA. At least the Greek imperative was altruistic, if we can believe the story.

There have been few examples in the public domain of a balanced approach to a just resolution of such injustices. One shining example is that of Mohandas Gandhi’s nonviolent breaking of the yoke of British imperialism in India, and more recently, the truth and reconciliation commission formed by the leadership of the recently departed Nelson Mandela of South Africa. The final outcome of rebalancing the extremes of apartheid are perhaps yet to be seen, but at least this represents a step away from the usual truth and retribution approach.

On a more immediate basis, recent political attacks on the president and a potential future candidate of the other party persuasion, tarred with Bridgegate, have become so much the same-ol’-same-ol’ as to have lost their effectiveness, if none of their vitriol, in swaying the undecided. The recent winter storm in Atlanta, labeled Snowmageddon, is an even more trivial example. The finger-pointing began immediately, as if in this best-of-all-possible worlds, it is unacceptable that people will do what they always do, which is to engage in self-serving behavior that accumulates the causes and conditions of disaster as quickly and predictably as expressways accumulate snow and ice.

In these situations, everyone wants to point a finger at anything other than their own nose. As usual, those who are least responsible receive the most heat. And those elected and appointed to anticipate and take action are now most interested in making sure this does not happen in the future, rather than debating their failures in the most recent past. A brief review of history shows the same pattern of incompetence, denial or ‘fessing up, putting the past behind and moving on, occurring on a regular basis—every decade or so in the case of local weather issues, about the same for international wars these days.

But the final lessons to be learned must necessarily take root in the heart of our being, on the personal level. Social activism comes second, third, or perhaps even fourth. Buddhism, and Zen in particular, does not profess to offer a top-down solution for society, but a ground-up approach to personal salvation and sanity in the midst of life. Of course, we want to observe the insidious effects of these societal influences on our own worldview and resultant behaviors, but dispassionately, in order to find liberation.

We are all guilty of selective memory, not just our leaders. Indeed, it may be one of the saving graces of human dignity, allowing us to mask the crushing inadequacy of our failure to live up to our own highest ideals. Think of the last time you had a part in a dispute with your fellows at work, family at home, or—Buddha friend—at the Zen center. Are you the one wanting to move on, or do you prefer to go back and review what happened in the interest of avoiding such another pitfall in the future? If you want to move on, not cry over spilt milk, is it because you are the one who spilled the milk? If you prefer to pick over those bones again, is it in the interests of justice, or just that you like to carry a grudge?

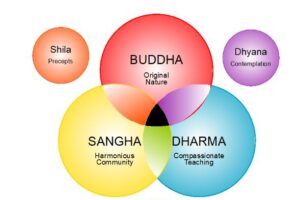

The social dimensions of Zen practice take a back seat to the personal. If we are not straight with ourselves, we will be of no use to others. In considering our behavior toward others, and theirs toward us, we need look no further than the Precepts and Perfections for wise guidance, as well as the Noble Eightfold Path. But the true value of this kind of second-guessing and problem-solving is what it reveals about the nature of the self. If we can come to an accommodation with the limitations of the constructed self—to even be capable of solving this dilemma—we may find an opening, a Dharma Gate, into the true self. If we live within the reality of this Buddha Nature, we will find that we do not hold anything against others, nor against ourselves. At least not for long, and the emphasis on the former. We are always our own worse critics, as is understandable. We know ourselves too well, even if we have everyone else fooled. But we should not be so hard on ourselves that we begin to doubt our potential for awakening. This does not amount to a license to kill, steal or lie, or any of the rest. It is a license to accept and admit to imperfection. As the great Chinese sage says (Hsinhsinming: Faith Mind; by Sengcan):

To live in this realization is to be without anxiety about nonperfection. To live in this faith is the road to nonduality, for the nondual is one with the trusting mind.

This trusting mind is not a simple matter of deciding to be more trusting in relationships. It is a deeper trust in existence itself, and the wisdom of bodhicitta, the body-mind, buddha nature, or true self. This self does not need to be, nor to be perceived as, perfect. We reserve the right to be wrong, in Zen. But we do not claim the right to not learn from our mistakes. Including what has been written here. It, the Zen life, is all one long mis-take. Master Sengcan concludes with this exclamation expressing exasperation with the effort to express buddhadharma:

Words! The Way is beyond language, for in it there is no yesterday, no tomorrow, no today.

We should not waste today in doubts and arguments that have nothing to do with this. Today is the only time we really have. “Today” is also only in this present moment.