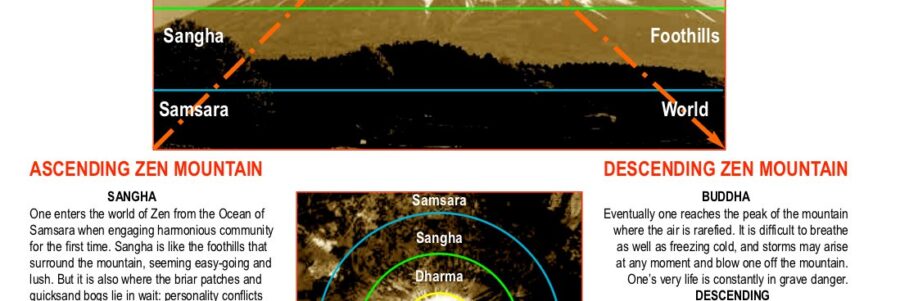

This article will complete the series of three essays on the Three Treasures, or jewels, of Buddhism, in their relationship to Zen practice. The first took up the idea and function of community in Zen — Sangha, the harmonious community. Next we looked at Dharma, the compassionate teaching. Finally, we will consider the jewel of Buddha, the original nature. We approach these traditional subjects from a somewhat unusual perspective, regarding them as different forms, or stages, of training, framed around the familiar metaphor of climbing a mountain (see illustration).

The inseparability of the three is a theme that we have seen running throughout, with the necessary balance to be struck in daily practice. But Soto Zen emphasizes a definite bias in favor of “buddha practice” —peak experience on the cushion — first and foremost.

Zen is for everyone, and lay practice is the future of Zen, but if it is Americanized to the same degree as the 24-7 news cycle, the echo chamber of talking points, and the bumper-sticker mentality that passes for insight these days, it has no real future.

zenkai Taiun Michael elliston, roshi

TREASURING BUDDHA

In the last segment we discussed what is meant by Dharma in Zen Buddhism. I confessed that, as with Sangha, I really don’t understand it. In Zen, we return to the cushion again and again to examine dharma, and when we leave the cushion, we re-enter sangha. Zen meditation, again, is of primary importance, being the only way to truly understand dharma, or to embrace sangha wholeheartedly.

If we were to title this section “Treasuring the Buddha,” we would be pointing to the historical Buddha Shakyamuni. But here we are simply referring to the buddha nature that is innate in all sentient beings, and which is the spiritual birthright of human beings. Birth as a human is considered the essential pivot-point, the requirement for awakening. Being thus, it is the responsibility of all human beings to be such a person. Sitting upright in zazen, or Samadhi, is the self-fulfilling method through which this transformation is most likely to occur, though it is impossible to establish a cause-effect relationship.

Buddha practice is visualized as the peak of Zen Mountain (see illustration). At the top of the mountain the air is rarefied; it is freezing cold. Frozen ice and snow make the walking treacherous, and the sky all around is pitch black, revealing the stars in all their adamantine sharpness and majestic indifference. One’s life is in immediate and intimate danger. A storm can arise at any moment and blow one off the mountain, on which one has only the most tenuous grip. Now is the time to step forward into the infinite abyss.

Returning to Matsuoka Roshi’s Dhyanayana; A Practical Guide Among The Ways Of Zen

from Mokurai, a collection of his talks from the 1970s and 1980s, we find more on zazen:

The Zen sects differ as to the purpose of zazen in that Rinzai views zazen as a means to enlightenment; whereas Soto views zazen as the expression of enlightenment. Nonetheless, the Rinzai, Obaku and Soto sects all agree on the prime importance of zazen.

So while there may be different styles amongst the sects of Zen, they come together around the central importance of upright seated meditation. In Soto Zen, it realizes its simplest application, in that it is not accompanied by study or koans or other verbal teachings from the history of Zen. It is considered complete, the Buddha’s seal. From Master Dogen’s effusive testimony regarding the experience and meaning of zazen, Self-fulfilling Samadhi (Jijuyu Zammai), we hear more testimony to this simple method:

Now all ancestors and all buddhas who uphold buddhadharma have made

it the true path of enlightenment to sit upright practicing in the midst of self-fulfilling samadhi

Those who attained enlightenment in India and China followed this way

It was done so because teachers and disciples personally transmitted this

excellent method as the essence of the teaching

In the authentic tradition of our teaching it is said that this directly

transmitted straightforward buddhadharma is the unsurpassable of the unsurpassable

Both Master Dogen and Matsuoka Roshi bother to make the point that it is necessary but not sufficient to do zazen; that one also needs to practice under the supervision of a “true teacher” or “master”; that in fact the two seem an indispensable and complementary pair. From Dhyanayana:

Secondly, all the Zen sects agree that it is important to study with an authentic teacher or Zen master. It is through a living interchange between master and disciple that a disciple comes to a mastery of Zen in his or her own right. This interchange, called heart to heart transmission, whether long or short in time duration, is only effective if the Zen student has prepared him or herself adequately through the assiduous practice of zazen.

And from Jijuyu Zammai:

From the first time you meet a master without engaging in incense offering bowing chanting Buddha’s name repentance or reading scriptures you should just wholeheartedly sit and thus drop away body and mind

It is implied that any true teacher or master will get out of the way of your practice. Specifically, by not distracting you from your practice of zazen with too much emphasis on ritualized sangha forms — incense offering, bowing, chanting Buddha’s name, repentance; and/or dharma study — reading scriptures. Or, for that matter, good works, administration, attachment to robes, socialization, making Zen palatable, or any number of other sidetracks and blind alleys. Matsuoka Roshi goes on to nail the personal dimension of practice, which trumps all the others, and ultimately puts them in perspective:

Bodhidharma, the twenty-eighth successor to Gautama Buddha, and the first Chinese patriarch, describes the characteristics of Zen study as:

A special transmission outside the sutras

No dependence on words or learning

Direct pointing to the mind of man

Seeing your real nature and living enlightenment

Master Dogen nails it more poetically, but with the same seminal and singular focus:

When even for a moment you express the Buddha’s seal in the three

actions by sitting upright in samadhi the whole phenomenal world becomes the Buddha’s seal and the entire sky turns into enlightenment

But — and with Master Dogen, as well as Sensei, there is always a but — it all depends on the individual’s diligence, endurance, and unwillingness to give up or settle for anything less than complete spiritual satisfaction. Sensei goes on to illustrate a syndrome that is seemingly a culturally-imbedded and stubborn trait, not exclusively of the Western mindset, but definitely exacerbated by memes such as the cult of the individual:

From a statistical point of view, by far the largest group of Zen practitioners are those who begin the practice of Zen, and then because of a lack of conviction, initial difficulties or a lack of self discipline, discontinue their practice. Most of the Zen Temples in the United States are populated by this latter group. And really, the Zen sanghas of historic and modern India, China, Japan, Korea and Viet Nam are, and were, probably very similar. It is very easy to see when observing this group of Zen practitioners who start, then stop, that there is no LIVING enlightenment in them. Surely, some of these people, depending upon their abilities, their consistency, their intensity and their duration of practice have differing degrees of insight into various parts of their lives; and this is a good, and important, effect.

This was true as of this writing, in 1985, and sadly, it seems even more so today. It is astonishing that Zen students who spend a few years, five or six at the most, in what appears to be diligent and dedicated practice, suddenly feel that they have gotten all they can get out of it, or that they are now qualified to go on their own and lead others, or even to instruct or correct their teacher.

During this time, their practice has amounted to part-time, not even half-time, as most of their time is devoted to family, friends, work, and other activities embraced as meaningful and normal in our consumption-driven society. Zen is for everyone, and lay practice is the future of Zen, but if it is Americanized to the same degree as the 24-7 news cycle, the echo chamber of talking points, and the bumper-sticker mentality that passes for insight these days, it has no real future. In a fifteen-trillion economy whose stability depends upon 70% consumption, it is clear that most practitioners are going to be caught up in the ever-accelerating cycle, and will come to regard Zen as just another commodity. If they do not find immediate satisfaction in their own practice, or their teacher, why, when the going gets tough, the tough go shopping. For another teacher, or another practice more accommodating to their perceived needs.

Sensei addresses this lamentable situation with the resignation garnered from experience:

Zen, however, does not radiate through them body, mind, and moment. They do not continually remember their own original nature, and act freely out of it and through it. That is a pity. I suppose that it is also the law of averages. Like anything effective on planet earth, Zen teachers from Shakyamuni Buddha to today have had to adapt the teaching as pointed at by Bodhidharma to the culture, language and status of those students of the Zen way that they seek to lead. They have also had to adapt their teaching to the level of gifts and to the level of intensity of their Zen disciples.

The real tragedy here is that these “come-and-go” or “wishy-washy” types, as Sensei would call them, are missing out on the opportunity to recover, or discover, their sacred birthright. As Jesus was said to have said when told of those who had rejected his teaching, “Their reward is with them.” Or as Shakyamuni remarked when told that some had come to debate at his last sermon (the Lotus Sutra), “They are free to go.” We have adopted, as our motto, Sokei-an’s expression: “Those who come here are welcomed; those who leave are not pursued.” This expresses the pragmatic balance to be struck.

It is impossible to convey the meaning and significance of zazen practice under a true teacher such as Matsuoka Roshi, but Master Dogen’s final words in Jijuyu Zammai come as close as one is likely to find:

Thus in the past future and present of the limitless universe this zazen

carries on the Buddha’s teaching endlessly

Each moment of zazen is equally wholeness of practice equally wholeness

of realization

This is not only practice while sitting it is like a hammer striking

emptiness before and after its exquisite peal permeates everywhere

how can it be limited to this moment?

Hundreds of things all manifest original practice from the original face

it is impossible to measure

Know that even if all buddhas of the ten directions as innumerable as the

sands of the Ganges exert their strength and with the buddhas’ wisdom try to measure the merit of one person’s zazen they will not be able to fully comprehend it

It is my fervent hope that all will climb to this inconceivable peak of Zen Mountain. And after — but only after, no premature proselytizing here — that they might descend once again into the marketplace, with benevolence-bestowing hands.