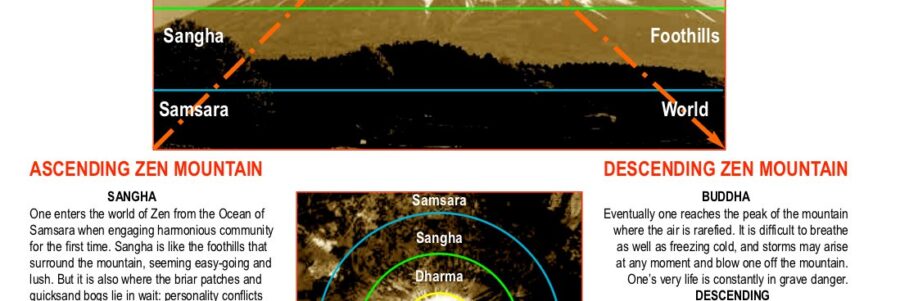

This article is the second in a series of examinations of the Three Treasures of Buddhism, in their relationship to Zen practice. The first took up the idea and function of community in Zen — Sangha, the harmonious community. This month we will look at Dharma, the compassionate teaching. Finally, we will consider the jewel of Buddha, the original nature. We will approach these traditional subjects from a somewhat unusual perspective, regarding them as different forms, or stages, of training, framed around the familiar metaphor of climbing a mountain (see illustration). Quoting from myself:

Dharma as a stage or form of training can be likened to the slopes of Zen Mountain. When and if we persist through the tarpits, quicksand and briarpatches of sangha practice, we may emerge on the other side of the foothills to begin the ascent of the more arid slopes of Zen Mountain. Leaving behind the warm and friendly confines of interacting with our fellow-travelers, we proceed up the steep incline, one finger-hold and toe-hold at a time. We may occasionally rely on our teacher or dharma brother or sister to belay us with a rope so as to avoid falling when we inevitably lose our grip, but we are pretty much on our own. The slopes of dharma are not as cushioning and comforting as the embrace of the lowlands and foothills of sangha, but they are cleaner, cooler, less entangling.

The inseparability of the three is a theme running throughout, with the necessary balance to be struck in daily practice. But we will continue the bias toward Zen’s “buddha practice,” the peak of direct experience on the cushion — zazen — as first and foremost.

People are conditioned to constantly seek excitement, entertainment, whether of melodrama, psychodrama — any drama will do.

zenkai taiun michael elliston, roshi

TREASURING THE DHARMA

Last month we explored the Buddhist ideal of Sangha in the context of the “only-don’t-know” mind of Zen. I confessed that I had come to the conclusion that I really don’t know what is going on the minds and hearts of others, particularly Zen students. When it comes to Dharma, I must provide a similar caveat. I really don’t know what it means. I don’t understand it. And that is the starting position of buddhadharma. Knowing that we don’t actually know.

Recently it occurred to me that a mere slip of the fast-finger syndrome, or a slight touch of dyslexia, is the only thing that stands between dharma and dhrama. The Sturm and Drang of drama may indeed be a meme of Zen practice in America today. People have become hyper-critical in a culture of constant conflict. College students these days grade their professors, guaranteeing conflict in the classroom. Conflict is exciting. People are conditioned to constantly seek excitement, entertainment, whether of melodrama, psychodrama — any drama will do. To fend off the suffocating anxiety of existence, the difficulty and boredom of daily life, including the tedium of simple Zen practice.

Dharma offers some relief from this situation. It points to the reality underlying the surface. Buddhadharma was the result of Buddha’s original estrangement, his disillusionment with the everyday concerns and engagements of his time, which were much less hyper than ours. The necessary balance to be found between zazen and practice in daily life applies to Dharma as much as to Sangha. As mentioned in the prior article, Dharma, technically, is the study of the spoken and written teachings.

But dharma does not exist in a vacuum, as a set of abstract teachings put down in words. The true meaning of dharma is not in the words. As with sangha, the deeper meaning of buddhadharma cannot be gotten from reading or discursive learning. Personal and direct insight is necessary to embrace the worldview that Buddhism values. The written record only points at the reality in front of your face. Buddha practice — Zen meditation — is of primary importance and efficacy, in “understanding” dharma as well as in embracing sangha. Buddha practice is found only at the peak of Zen Mountain.

Descending Zen Mountain is different from ascending. Both dharma and sangha look very different from the perspective of practice-experience on the cushion. Entering sangha from the outside world, it appears as a sanctuary, a group of like-minded individuals; dharma initially appears as a body of knowledge to be learned. Re-entering sangha from the perspective of buddha practice, it appears as one’s own family; dharma as recorded is revealed as the poor shadow of a reality beyond words, beyond grasping.

The inseparability of dharma from buddha and sangha becomes crystal clear, as the foremost aspect of each tripart, but particularly of dharma. Again, the three-legged stool.

The most difficult dharma is often said to be that of marriage, considered by some the fundamental dyad of society. The dharma of married, or family, life is the most difficult to learn. This may be one reason why the practitioners of Zen were often celibate, living a monastic life that eschewed normal family entanglements. It is a kind of simplicity imposed from the outside. Finding the simplicity of family in the midst of it is a difficult trick to turn.

Let us turn to written words of our founding Zen master, Dogen Zenji, in Fukanzazengi:

You should stop pursuing words and letters and learn to withdraw and reflect on yourself

When you do so your body and mind will naturally fall away and your original Buddha-nature will appear

Here we find the dharma, in its sense of truth, expressed as instruction, or skillful means. Pursuing words and letters is not the same as reading. It is reading with the hope, which Master Dogen is implying is ultimately vain, that we will find the dharma, in its meaning of spiritual insight. Instead, the great genius of Zen encourages us to simply reflect upon oneself, which seems to be the surest way to become mired in mindless boredom. Withdrawing may be the key here. Whatever it is that you find boring about yourself, if youwithdraw from it, you may find that something else is in play. What is boring may be your misinterpretation of what you mean by your self. Master Dogen then goes on to remind us that there is no time to waste; this may take some time:

If you wish to realize the Buddha’s wisdom you should begin training immediately

From the Master’s Self-fulfilling Samadhi (Jijuyu Zanmai), we hear:

you will in zazen unmistakably drop off body and mind

cutting off the various defiled thoughts from the past

and realize the essential buddhadharma

So dropping off body and mind (shinjin datsuraku) is key to apprehending the dharma. What do you suppose that means? It cannot be simply ignoring the body and mind as an act of willpower, as Zen’s truth is experiential. Defiled thoughts here would include such concepts as attaining buddhadharma by changing one’s mind or viewpoint. Defilement means conventional, discriminating thinking, and does not refer to the content of the thought, as in vile or degrading. Defilement is what we reduce buddhadharma to when we think we can understand it with the intellect. Thoughts from the past would include all of those regarding dharma as a concept up until the moment of insight, when all such thinking is cut off in the moment of clarity beyond thought. The essential buddhadharma implies that whatever buddhadharma we thought we understood until that moment was not the essential truth.

Now all of this may imply to the dear reader that this writer is claiming profound insight not accessible to the hoi polloi, which is how much writing comes across these days. So let me fess up to my poor, or at least ordinary understanding of Dharma. It perfectly compliments the degree of my grasp of Sangha & Buddha.

If I see a member of the sangha practicing zazen diligently, and not getting bogged down in the interpersonal issues, real or imagined, with other Sangha members, then I don’t worry about them. If I see that they are not reading too much, not overly eager to discuss and display their grasp of buddhadharma, but are more interested in others’ understanding, then I don’t worry about them.

The technical definition of Dharma must be replaced with a simple one of truth. Truth transcending memes of the culture that hold that Truth is captured in scripture, sacred texts, commandments, rules, laws of the land, as well as philosophy, science, psychology, religion, the arts and so forth. Compared to these truths, which are based either on belief or confirming evidence, or a combination of the two, in Buddhism the ultimate truth is based on the identification of the self with the transformative experience of insight. Dharma, as truth, in Zen, is experiential. Which is what makes it accessible to all.

But the very experiential nature of this truth, with its reliance on first-person evidence, is what creates the mystique surrounding Buddhist awakening. As Matsuoka Roshi reminds us in the second volume of his collected talks, Mokurai: Dhyanayana, A Practical Guide Among The Ways Of Zen:

Zen first gained a popular foothold in the cultural life of the United States a half century after Soyen Shaku’s visit. Among some of the intellectuals of that time, among the circle of beat poets and authors, Zen became something of a philosophical fancy. It was portrayed in jack Kerouac’s book, On The Road, as a philosophical motif in the dialogue of a group of itinerants touring across America against a backdrop of their personal drama and social commentary. For the beat generation of the ‘fifties Zen was used as nothing more than a justification for new or non conventional behavior. This was called “Beat Zen.” It was never really a school of Zen as are Rinzai and Soto, which are both founded in a tradition of serious practice. Nonetheless, “Beat Zen” did much to focus popular and literary attention toward Zen, just as the writings of Dr. Daisetsu Suzuki, a disciple of Soyen Shaku Roshi, did much to focus academic attention toward Zen. And so, from the popular discussion of Zen without direct experience that ensued, Americans created a mystique around Zen from all they had heard.

Another early influence that had a distorting effect was that of Alan Watts, who pointed out that Zen does not represent a religion, in the Western sense of being based on belief; and that it is not a philosophy, exactly, but more a psychotherapy. This, I believe, colored the perception and conception of Zen in the Western mind, and with the other influences above placed Zen in a New Age niche from which it is still struggling to extricate itself.

One persistent meme derived from these referents is an informational definition of the function of Dharma — as content expressible in words. This perception feeds into the same “birds of a feather/fun to get together” — talk about the dharma, debate, and share each other’s expertise and go home feeling a little bit more enlightened — mentioned previously in the context of the kaffeklatsch sangha.

This characterization of Dharma as something that can be studied also lends to competition, one-upsmanship, and other entertainments of the monkey mind. It suggests, in egalitarian fashion, that all opinions are equal, but the more informed can hold sway with studied regurgitation of facts. It also implies the notion that, Why have a teacher when I can study all that has been written about buddhadharma?

Of course, one cannot in one lifetime possibly read all that has been written over 2000 years, much of which is not yet translated into English. Nowadays one could hardly read what is available in English. Most of which will turn out to be “publish-or-perish” commentaries by authors of dubious direct experience, and a growing body of literature about Buddhism or Zen, outside the realm of actual practice esperience. Not to put too fine a point on it, but much of the literature from various professions that have co-opted Zen seems to be driven by less than altruistic motives, let alone Buddhism’s Precept to not spare the dharma assets.

Buddhadharma is not offered up for debate and speculation, however interesting and elevating. It is not intended to be intellectually parsed to support the careers of careerists in the professing profession. Nor is it meant to support the offerings of the helping professions in counseling, life coaching, psychology and psychiatry.

Buddhadharma exists for one purpose only and that is to point at the truth (dharma) that Buddha and the Ancestors experienced, and transmitted to the next generation. For the first four centuries or so it wasn’t even written down, one suspects to prevent it from the predations of writers, who even then could not resist tinkering with it to their own ends.

Dharma is not merely a cohesive, internally-consistent philosophy to be compared and contrasted with other philosophies as just another entrée on that already-overloaded groaning board. It is not one in a quiver of many arrows to be bent to the purposes of those out to save the world, individual souls, or other people’s sanity. It may be argued that it is intended to save one’s sanity, but that term would have to be relieved of its social baggage to accord with what might be considered sane in Zen.

Although in marketing terms, Soto Zen has to represent one of the most venerable and respected brands in history, it is not designed for its proponents to profit from the enterprise, nor to bask in the glow of its aura while selling delusion. This is the easiest claim to bring against a practitioner, accusations of greed for fame and profit, but any thinking person who takes a cold and calculating look at the market for Zen would quickly seek greener pastures elsewhere. Dharma does not do avarice.

Dharma challenges conventional mores and standards as to what constitutes learning, or knowledge — what is worth knowing and what simply constitutes a mind full of useless information. This culture’s worship of the latter, and the concomitant ability to instantly recall reams of trivia, is demonstrated by the persistent poularity of game shows purporting to reward the intelligence of the winners.

But true intelligence is not the accumulation, storage and retrieval of witless tons of information. That is a warehousing operation, and efficiency is its alpha and omega. It is not at all necessary to understand information to regurgitate it on demand. The recent victory of a computer over two of Jeopardy’s champions drove this home with a vengeance. Those who have been envied, admired, feted — or in cases of the idiot savant, pitied — for their near-miraculous recall, can testify that total recall can be as much a curse as a blessing.

I once had a boss who claimed to have photographic memory (in a vain attempt to buttress his opinion of what had gone wrong with a project). I knew better from years of working with him, but my first reaction was, Oh that is too bad; I feel so sorry for you. Anyone who actually had total recall would be cursed to relive every petty and ridiculous memory that they have ever had since consciousness arose. In my case, most of it is not worth remembering.

When this attitude is applied to Zen Buddhism, it becomes a pathetic caricature of Zen. It is the height of irony that the only body of teaching that is intended to help divest, and disabuse ourselves of, culturally-conditioned, obsessive-compulsive approaches to learning, is turned into yet more grist for the data mill. In extreme manifestations of intellectual hubris, witnessed repeatedly in history, it becomes an overweening emphasis. Erudition is a brief slide away from pedantry — slavish attention to obscure facts or details, undue displays of learning. This is widely ridiculed, as missing the point entirely.

Zen Buddhism, with its direct approach to physical meditation, the non-separation of body-mind, is regarded as the development of true intelligence. Intelligence is typically defined as the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills (New Oxford American Dictionary). Buckminster Fuller defined it as the ability to extract general principles from particular case experiences. In cultural evolution, it is driven by linguistic ability to transfer information to the next generation.

Intelligence in Zen would partake of all of these dimensions to a degree. But it begins with a more fundamental definition that separates truth, the fundamental object of intelligence, into two realms — the relative and absolute, or conventional and transcendent. It poses questions: What is our intelligence for? What is worth knowing and what is not? In fact, Zen’s starting point is, What is knowing itself?

The direct apprehension of buddhadharma begins with questioning what we think we know. It does not begin with a campaign to gain more knowledge, however arcane or high-minded, though that is the usual entry level for most people. The process that occurs naturally in Zen meditation is one of stripping away opinions, beliefs, theories, ideas, philosophies, and concepts that we have learned about reality, so that it becomes possible to have a direct experience of reality. This latter kind of knowledge would then be considered truth, as opposed to opinion. It is uncovered through a program of unlearning.

But Zen opposes the very idea that our direct experience, familiar to us in ordinary consciousness, penetrates to any level of insight that could be considered true. The very sense-data provided to the nervous system is regarded as biased and unreliable. When such information is processed by the brain for analysis, resulting in perception, it is even more skewed. And when unconscious mental formations come into play from past experience, it is further distorted. One can have unreasoning fear, for example, or “irrational exuberance,” for another, which has no connection with present reality. Yet it can overlay our perception, and condition our actions, with unintended consequences.

From the classical Buddhist canon — which most scholars and otherwise normal folks would regard as comprising the Dharma, the scriptures of Zen — we can find the First Sermon, which introduces the Four Noble Truths and Eightfold Path; the 12-fold Chain; the Six Paramitas; and so on. From the first Noble Truth that existence itself is of the nature of suffering, to the Precepts (shila) Paramita (perfection), we find that all are pointing at truth and taking action in the context of the truth. Zen’s Dharma is sometimes considered pessimistic, as it does not promise us a rose garden nor rebirth in paradise.

But Zen Buddhism promises something infinitely more useful: a method for our own salvation, and that of others. There is actually something to do in Zen, something that works in one’s daily life to mitigate the unnecessary suffering that we inflict upon ourselves and upon others. The teachings are all inter-connected in ways that can be seen as actionable. For example, the relationships between the Three Treasures or Jewels, and the Paramitas:

Buddhadharma is all about the interfaces between the teachings of Buddhism. For example, when we look at the Three Treasures in an overlapping Venn diagram, we can see that the overlap between Dharma and Sangha would indicate the application, and hopefully perfecting (paramita) of skillful means (upaya). Between Dharma and Buddha we would find contemplation (dhyana), perfecting of meditation to resolve the relation of our original nature to the compassionate teaching. Between Sangha and Buddha we may place the perfecting of Precepts (shila), as a way to maintain harmony in the community.

Likewise, we can relate the tripartite division of the Eightfold Path to the Three Treasures: right conduct (speech, action and livelihood) being the outer mark of the harmonious Sangha; Right Wisdom (view and thought) being the manifestation of true Dharma; and right discipline (effort, mindfulness, meditation) the inner workings of Buddha.

So it is necessary that when we do come together, we focus on the central challenge of life, that of resolving the basic dilemma of existence through direct experience. Again, the rewards of engaging in philosophical speculation, reading and sharing thoughts on the latest popular book on the best-selling list, snappy repartee and mutual admiration, cannot be gainsaid. But the true Dharma gets lost in the excitement. Dharma is not in the words, and no matter how relentlessly the texts are massaged, the cool water of the Dharma is not going to be wrung out of them, like so many used washcloths.

Zen is nourishing, like rice. It is refreshing, like water. What Zen offers the whole ocean in one gulp. Stop complaining about your thirst, and begin drinking. If hungry, eat Zen.