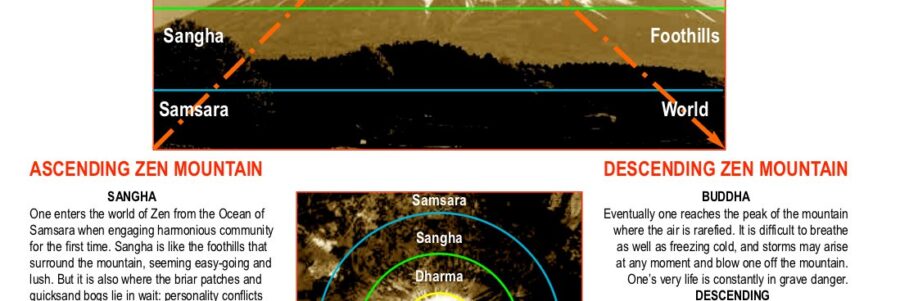

This article will introduce a series of three examinations of the Three Treasures, or jewels, of Buddhism, in their relationship to Zen practice. The first will take up the idea and function of community in Zen — Sangha, the harmonious community. Next month we will look at Dharma, the compassionate teaching. Finally, we will consider the jewel of Buddha, the original nature. We will approach these traditional subjects from a somewhat unusual perspective, regarding them as different forms, or stages, of training, framed around the familiar metaphor of climbing a mountain.

The inseparability of the three is a theme that we will see running throughout, with the necessary balance to be struck in daily practice, much like Philip Kapleau’s Three Pillars of Zen, the 3-legged stool metaphor. But we will emphasize a definite bias toward Zen’s “buddha” practice, the peak of direct experience on the cushion — zazen — as first and foremost in importance and efficacy. As the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers would say, Zazen will get you through times of no sangha or dharma a lot better than sangha or dharma will get you through times of no zazen.

The Buddhist community, sangha, is not intended to reinforce similarities. Its members are not necessarily like-minded. The Order was, from its beginning in India, designed to cross all lines of the cultural community

Zenkai Taiun Michael Elliston, roshi

TREASURING THE SANGHA

Last month we explored the “only-don’t-know” mind of Zen — not-knowing as an approach to Buddhist wisdom. I confessed that I had come to the conclusion that, when I think I really know what is going on the minds and hearts of others, particularly students and members of the sangha, I really don’t know. I’m not a mind-reader. Nor the Shadow.

In his first written tract after returning to Japan from China at the tender age of 25 or so, Master Dogen recorded basic instructions and some philosophical underpinnings of zazen for his students to use as reference, at their request. One of the lines says something about “forsaking all delusive relationships, setting everything aside” in beginning meditation. The part about setting everything aside is difficult enough, but I have to really question how one would know whether or not a relationship is delusive, and should be forsaken; or whether it is not. Is there any relationship that is not, in some way, delusive? I digress.

This time, I would like to share with you some insights, admittedly with a pro-teacher bias, regarding sangha and students, particularly American or Western students of Zen. I will presume to speak in the generalized context of all Zen teachers and students for sake of simplicity, and to depersonalize any suggestions made. But these are my opinions alone, and do not claim to represent other teachers you may have encountered, or those you may encounter in future. Please bear with a long bit of introduction and history.

I came to Atlanta in 1970, with the practice robe Matsuoka Roshi gave me and one zafu under my arm. The same year, Matsuoka Roshi moved to Long Beach and established the Temple there, with Kongo Roshi taking over the Zen Buddhist Temple of Chicago, established in the 1950s. I “kept my light under a bushel” for a few years, while re-establishing my life, having left behind the world of academia, and my first marriage, in Chicago. Later, once I had a suitable place to live, my children rejoined me, and my ex-wife moved to Atlanta to be near them. I had embarked upon a new career in the world of consumer research and design for new product development, meeting many new people, and cultivating a new community of friends, as well a new marriage.

In 1974, I first began offering classes in Zen meditation at the Cliff Valley Unitarian Universalist Congregation of Atlanta, schlepping two oversize trash bags full of zafus into the building every week. In the years since, I offered regular public meditation in our home (not a good idea), and in various storefronts and other locations, managing to achieve some consistency of practice, with very little disruption in continuity. And, incidentally, with no income from Zen (really not a good idea, as it turns out).

Eventually, in 1977, we had established a large and committed enough group to incorporate the Atlanta Soto Zen Center (ASZC) as a 501c3 under the state charter of Georgia. Later, in the early 1980s, we found a space in Little Five Points that we could afford to rent. Others began contributing financially to the cost of overhead (about $500 per month in those days) and I, as the registered agent of the corporation, continued to match the largest donor each year (regulations of the IRS prohibit the agent from being the largest donor for obvious reasons).

During the 1980s, more attendees became regular members, and with very little formal structure, excepting bylaws and a nascent board of directors, the local sangha grew. The Disciple group also grew as Matsuoka Roshi gave me permission and the requisite ceremonies and certificates of his formal recognition to take on my own students. Toward the end of the 1990s, we had a rather full schedule, and had developed a few affiliate groups; I was asked by seniors to become full-time. This meant I had to find a way to retire from my research and design business, stop pursuing national accounts, and needed supplemental income from the sangha (my finances were insufficient to retire).

Over the years, literally thousands of individuals have come and gone, often crediting us, ASZC, with their first real exposure to genuine Zen practice of any formal sort. Many have stayed in touch, though they have scattered to the four corners of the globe (one of my favorite, if inaccurate, expressions). Several Disciples moved on in life, of course, and a few established substantial sitting groups and Zen centers where they landed. One left as early as 1980 and, returning to Nova Scotia, established our affiliate there. He will return for his term as Shuso (Head Monk) in residence during Ango (Practice Period) this month. Over thirty years later, he is taking the next step in fromal prerequisites for transmission as a Soto Zen Buddhist priest. Teaching us all, by his great example, the practice of patience and humility. He has taken up the life-long view of Zen.

Others have left under less cheerful circumstances, but such is life. Not everyone is cut out to practice Zen, whether in an informal or formal setting. We are accustomed to shopping around these days for everything from a new pair of flip-flops to a husband or wife. There’s an app for that.

I find it clarifying to think in terms of the Three Treasures, when attempting to analyze or understand behavior of Zen students. Of course, balance is needed between the three, as the legs of Zen stability. Sangha is community, with all that that implies about the social dimensions of Dharma (e.g. Precepts and Paramitas), with regards to sangha members, including one’s teachers. Dharma, technically, is the study of the spoken and written teachings. Buddha is the direct experience of Dharma, on or off the cushion.

Finding balance in practice between these three is a matter of personal discernment, adapting to what is required by one’s specific sangha and place of practice. We do not practice Zen with the sangha we choose; we practice Zen with the sangha we have. Including, like it or not, the teacher’s personality, training, and predilections. Eventually, the three are seen as facets of one gem. Buddha = dharma = sangha = buddha.

In a recent conversation with one of my teachers, she reminded me that in this country, we have cultural “models” — you may prefer memes, a term currently in vogue. These in some measure affect individual attitudes, perceptions and preconceptions regarding Zen. One powerful influence she suggested is the Protestant church, with its emphasis on community in the sense of fellowship. Of course, there is also the underlying identity of the select, whose souls are saved, versus those going to hell, a stubborn meme. Gradually it is giving way to a more ecumenical embrace of other salvation religions, I am told. Another, the Religious Society of Friends, aka Quakers, who allow as how individuals can directly experience Christ, or God. Their practice of publicly sitting in silence, is similar to meditation, but punctuated by the occasional outspoken revelation.

One persistent meme derived from these referents is a social definition of the function of community, with positive connotations of friendship (reinforced by sanctity, as the body of Christ). Another is the egalitarian ideal of the (Quaker) congregation, largely eschewing authoritarian leadership. The same may be said of Unitarianism, which seems to favor consensus of the many over authority of any one, including even that of Christ.

Some may question why Zen Buddhists would bother to gather as a group at all. Why not just retire to a cave and contemplate the buddhadharma? The answers are found in the cultural context. We are social beings, comfortable flocking together with birds of similar feather. The concept of similarity usually reflects the causes and conditions of one’s birth: race; ethnicity; language; physical or sensory impairment; along with stereotypical traits: age group (talkin’ ’bout my generation); education; physical fitness and body type; attractiveness; even or especially relative financial success. All understandable, self-selecting filters, for the parameters of a community in which one can feel a sense of belonging. Opposites repel. But that which brings us together separates us from others.

The Buddhist community, sangha, is not intended to reinforce similarities. Its members are not necessarily like-minded. The Order was, from its beginning in India, designed to cross all lines of the cultural community, in those days codified into a rigid caste system. All were welcome to join the sangha, from any level of society, regardless of ability to pay, or to perform. It was, eventually, as inclusive as practicable, not exclusive.

It also challenged traditional memes — cultural mores and standards — as to what constitutes true home and family; who are loved ones, and who the outcasts, if any. It taught compassion and forbearance, especially with the failings of others. Occasionally, members had to be excluded, mainly for the same reasons some are today — fomenting disharmony in the sangha. Buddha’s own cousin, Devadatta is known to have betrayed, and attempted to assassinate, him. Huineng, Dogen, and others were vilified by factions.

Today, the Zen Buddhist community is still something of an anomaly, in the context of what is conventionally meant by community. Sangha is much like an amoeba, constantly shape-shifting. It is not limited to the local yokels. Another metaphor: Zen practitioners are like a guerilla warfare squad, coming together from time to time to meditate; then dispersing to confront the battles of everyday life as undercover resistance fighters.

So it is crucially important that when we do come together, we focus on the central challenge of life, that of resolving the basic dilemma of existence. Our method, the alpha and omega of Buddhist praxis, is to probe this mystery on the cushion. When we find that we are gathering for other reasons, and driven by other needs, however cherished, it is no longer a Zen Buddhist sangha. It may be a community, and it may be harmonious, but it exists for other purposes. Not that there is anything wrong with that.

People often come looking to Zen centers for the creature comforts of keeping company with like-minded fellow travelers. Some may value the rewards of engaging in philosophical speculation through reading great books, especially the classics of Zen. But other organizations are quite capable of providing fellowship, bonhomie, networking opportunities, programs for singles, parents, children, and intellectual enrichment. There is certainly nothing wrong with a sangha meeting some of these peripheral needs.

But no other institution is as competent and capable of providing the conducive environment, and robust program for the direct learning (or unlearning) process that is uniquely represented by zazen, or shikantaza. What a Zen sangha offers is very simple. But it is very difficult for people to sustain. It is easy to develop expectations, become disillusioned or disappointed, and quit too soon, to go wandering in other pastures.

Sangha provides psychological and social support to its members over the long term. It helps the individual sustain their effort long enough to come to personal insight, as well as to transcend any overweening dependency on sangha as such. Let us continue to treasure the Sangha, in harmony with Dharma and Buddha. We do so in support of our mission of propagating genuine Soto Zen, through the buddha-seal — the meditation of Master Dogen, and of Shakyamuni Buddha.

This is the mission that we in the lineages of Matsuoka Roshi, Uchiyama Roshi, and Suzuki Roshi have inherited. We cannot allow ourselves, or others in our sangha, to become distracted by other missions, however appealing and satisfying to our cultural demands, and personal self- image.

Zen is bland, like rice. It is tasteless, like water. What Zen offers is not simply another entrée on the spiritual smorgasbord. If it were, it wouldn’t have lasted for 2500 years.