Green Mountain Zen Center is one of our affiliate centers, in Huntsville, Alabama, under the direction of Practice Leader Kawa James Gordon. Each fourth Sunday of the month we have a discussion by telephone, usually about a published text. Usually, Green Mountain students read the material and prepare questions before calling me at the appointed time. I read the material that day and do my best to respond to the questions. So far so good.

The current subject is the book “Buddhist Cosmology – Philosophy and Origins,” by Akira Sadakata, Kosei Publishing Company, Tokyo. This is a rather strange book to be studying in the context of Zen, as it deals with really arcane and speculative cosmic concepts of classical Buddhism. Quoting copy from the back cover:

This extensively researched and illustrated volume offers Western readers a rare introduction to Buddhism’s complex and fascinating views about the structure of the universe. The book begins by clearly explaining classical cosmology, with its symmetrical, India-centered universe and multitudinous heavens and hells, and illuminates the cosmos’s relation to the human concerns of karma, transmigration, and enlightenment.

The blurb concludes with the reason it may not be so strange a selection:

Finally, the author shows us how this ancient philosophy resembles the modern scientific view of the cosmos, and how even today it can help us lead more fulfilling lives. Well, that sounded better, so naturally, I read the final chapters first.

The important point for us is that reality can be directly experienced, mainly through meditation. We investigate whether or not this idea of a soul holds any water, when we sit on the cushion.

Zenkai taiun michael elliston, roshi

Last night we discussed the first chapter, “The Structure of Matter and the Universe” (the author wanted to get this out of the way quickly and get on to the interesting stuff). After briefly reviewing the first few centuries of Buddhism after Buddha’s death, including division into “eighteen or twenty schools, which are collectively called Abhidharma Buddhism,” the author introduces the reform movement in the first century B.C.E. Self-named as the “Mahayana (Great Vehicle),” it labeled Abhidharma Buddhism “Hinayana (Small or lesser vehicle).” Mr. Sadakata contrasts three principles of each school, which was the focus of the Green Mountain group’s question. The text (page 19) reads:

Buddhist cosmology according to the Hinayana tradition centers on (1) the realm of Mount Sumeru, (2) dharmas (the Buddha’s teachings), and (3) the notion that the Buddha (Sakyamuni) is a historical person. In Mahayana Buddhism, (1) the various “buddha-realms” are more important than Mount Sumeru, (2) the Buddha (or buddhas) takes precedence over dharmas, and (3) the Buddha is a suprahuman (cosmological) existence. As we shall see in part 2, Mahayana views thus changed Buddhism from a philosophy to a religion.

Jim expressed the main question raised by point number (3). Zen regards Buddha as an historical person, rather than a deity, apparently more in line with Hinayana (HY) Buddhism than Mahayana (MY), under this comparison. I ignored the focus on number (3), and addressed points numbers (1) and (2), buying time for my brain to work on an intelligent response to the actual question.

In brief, and from a non-scholarly perspective on numbers (1), the HY realm of Mount Sumeru was replaced by the MY “buddha-realms” much as the flat-earth theory was replaced by Newtonian mechanics and later cosmologies based on discoveries of Hubble and others. We can take both HY and MY models to be what one might come up with, based on the limited access to astronomical technology of the times, the necessities of Buddhist training, and the mathematical bent and aesthetic proclivities of Indian ethnicity.

Nowadays, with the overwhelmingly big picture of the universe provided by ever-more-acute and penetrating eyes on the heavens that have been deployed, we might tend to find these ancient speculations quaint. But we have the same problem: how do we square the teachings of Buddhism with the emergent vision of the vast form of the universe?

In points number (2), MY stresses emphasis on buddhas over dharmas. In HY, dharmas, the spoken and, later, written teachings were reified as the transmission of enlightenment. One’s degree of understanding depended on one’s absorption in study and assimilation of the verbal teachings, rather than the “special transcription outside of scripture’ later transmitted by Bodhidharma to China.

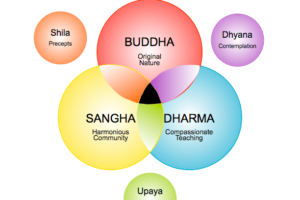

The MY reformation reminded practitioners that this direct experience (buddha) of reality preceded the expression of it (dharma) in Buddha’s own life. And that the Ancestors all had relied upon this direct experience, which gave them the authority to interpret — and even to contradict — the dharma as handed down in verbal form.

Finally, to point numbers (3). HY interpreted Buddha as an historical person, one who had a profound insight, and expounded this insight to his followers. Owing to his skillful means, they were able to understood it and to come to a degree of the same realization, depending upon their intensity of practice and natural ability. Note that no one claims the same depth of awakening as Buddha, but this is a sign of deep respect for the Founder who had no teacher. It does not imply that Buddha was different from them, or from us.

That MY interpreted Buddha as a “suprahuman (cosmological) existence” does not mean that the reformation elevated him to the level of a god. Siddhartha Gautama, sat down under the bodhi tree that night, what stood up was “buddha”: no longer identifiable as that other person, that “human” being.

“Buddha,” which comes from the Sanskrit root “bud,” meaning “awake” denotes an “awakened one.” When Buddha was asked “what” he was, he said: “awake.” This means that he had awakened from the dream of being “Siddhartha Gautama,” prince of the Shakya clan, white, male, Caucasian, Indian, six feet tall, brown skin, black hair with topknot, et cetera et cetera et cetera. All such identifiable and identity-related attributes were rendered mere circumstance, and in a very real sense, arbitrary. That is, they had no causal or other relationship to what had transpired. (This is why, for example, statuary and paintings representing buddhas and bodhisattvas—which Buddha was, unbeknownst to him, up until his awakening—are usually androgynous. Buddha-nature is not gendered.)

So Buddha had transcended humanity. Being awake meant that he had been released from the dream of being a human being. We were asleep last night and awoke this morning, and are still awake, and we know the difference. Buddhism posits that we can wake up from this “awake” in a similar sense; and that awakening is at least as different from this awakened state as it is from sleep.

But the suprahumanity of Buddha does not mean godlike in the religious sense — that he had become, or been revealed to be, unique. Christ is considered “God made flesh” in Christianity (in Buddhism, Jesus is considered a Bodhisattva), but Buddha is considered the epitome of humanity in Buddhism. In fact, the famous statue of Buddha touching the earth at the peak of his awakening symbolizes the down-to-earth quality, accessible to all, of his profound experience.

Suprahuman means that although a human being, we can wake up to a reality in which that label no longer has the same meaning. The human body, birth as a human, is considered essential to awakening, but the human being, per se, does not survive it. Buddhist awakening necessarily transcends what is meant by “humanity.” Buddhahood may be said to be a form of existence, but it is not limited to human attributes, nor is it humanly understandable. Nor is it another, separate existence. This is why Master Dogen said awakening does not happen to humans, but only “buddhas together with buddhas.”

The author’s concluding interpretation that “Mahayana views thus changed Buddhism from a philosophy to a religion” (without reading the detail in Part 2) should not be colored by our current definition of “religion.” Religion in India of the time would likely not resemble anything like organized religion today. It is important to remember context. Buddha was not a Buddhist. We hold that Buddha was a human being much like us, and that Buddhism is not a religion like Christianity, Islam or Judaism.

The change effected by the Mahayana reformation appears to be that Buddhism became a path of salvation, rather than a philosophy dedicated to understanding reality. The way to salvation is through the transcendent experience of Buddha’s awakening. But individual salvation is not considered possible; thus, “Greater vehicle.” The vow to save all others before oneself, the Bodhisattva vow, is a religious vow, not a philosophy.

CONCEPT OF SOUL

A response to a recent email from one of our members is related to this discussion of the transformative experience that became the basis of Buddhism. Remember, Buddha was not a Buddhist. His experience was not hampered by such ideas. The email asked:

Sensei,

My understanding is that there is no permanent, enduring, unchanging soul. If that is the case, is there a soul in existence in the exact moment we are in or is there no soul? If there is a soul, what is it, energy perhaps?

Any teaching that you can provide, will be very appreciated.

Thank You, TY

Dear TY:

In brief, there is a “true person” in Zen, which is what makes you different from me and vice-versa. This true person is the only one who can do what you can do, and can, for example, practice “secret virtue”: actions that no one else sees, but are beneficial to self and others.

The Buddhist idea of personhood needs the context of the “three bodies” starting with the physical. This is the Nirmanakaya, or transformation body of Buddhism, the physical body, which is always in transformation. This person is both body and mind, the sum total of karmic influences and present causes and conditions, from this and past lives. One’s karma is not individuated but shared with others. Personality includes specific traits (temperament) inherited from parents, habits and character traits that are learned, views developed as one matures in life, and capacities and talents unique to each individual.

The Dharmakaya, essence, truth, or causal body, is not limited by this unique personal self, but transcends self and other. The Dharmakaya can be experienced, for example, as a realization that comes from one’s practice, particularly from meditation. When this comes about, there is no separation of the Nirmanakaya and Dharmakaya, and this is the experience of Samboghakaya, the subtle or enjoyment body. The Trikaya, or three bodies, represent a way of looking at personhood in tripartite aspects that actually cannot be separated, and so is simply a useful manner of speaking. However, it does point to a transformative experience: from the normal state and experience of ignorance, to that of insight, or emptiness of the constructed self.

The concept of “true self” in India of that time may be somewhat similar to the Christian idea of soul, but not exactly (there was no Christianity at the time). The atman is a self-existent entity, that puts on life after life much as we change clothes. Over time, including multiple lifetimes, the atman evolves to finally merge with the universal godhead, Brahman.

Buddha taught that he did not find any evidence of “atman” (or soul) in his experience, in fact quite the opposite. Buddha instead found this idea to be a fantasy. Later teachers, such as Nagarjuna, demonstrated that atman is a proposition that can be reduced to absurdity through logical analysis. Same for religions’ “eternal soul.”

The important point for us is that reality can be directly experienced, mainly through meditation. We investigate whether or not this idea of a soul holds any water, when we sit on the cushion. This is what is meant by “The Great Death,” or dying on the cushion. The idea that the soul may be thought of as “energy” is a work-around: it seems to address the question, but actually only changes the terms, substituting energy for soul. Because in Buddhism that which has form is of the nature of emptiness, or the material is just the immaterial (the immaterial just the material), of course everything can be considered a form of energy. But every “thing” is not separable from other things, and each and every thing is changing at all times.

Thus the true self is changing at all times as well. It is not necessary to add a “soul.” In this universe of change we cannot find any permanent thing. This is a conundrum. Please consider this on the cushion.

I know this does not really answer your question. We can discuss further, but this is a fundamental question that cannot be answered in words. The words merely point at the answer to be found in your direct experience.