Road-map to Enlightenment

ASPIRATION & ZAZEN – ROADMAP TO ENLIGHTENMENT

In the last few months of 2010 we discussed the topic of anger and anxiety and their relation to zazen, subjects that comes up often in dokusan and discussion. This month let us take a look at aspiration, and its relationship to expectation in our practice of zazen, in the context of next year’s program of daily practice, retreats and special events sponsored by the Silent Thunder Order and hosted by Atlanta Soto Zen Center and Affiliate network of sanghas.

The difference between aspiration and expectation may not be obvious, nor may its relevance to Zen practice be clear. Microsoft Word’s perfunctory dictionary defines aspiration as “a desire or ambition to achieve something” and expectation as “a confident belief or strong hope that a particular event will happen.” It also refers to “a mental image of something expected, often compared to its reality.” And, lastly, “a standard of conduct or performance expected by or of somebody.”

In Zen, we can maintain a personal aspiration, without having it devolve or deteriorate into an expectation. This is a fine line.

zenkai taiun Michael elliston, roshi

So on the personal level, an aspiration may be distinguished from an expectation in terms of how definitive and specific it is, i.e. from “something” to a “particular event.” The inevitable comparison to reality moves the dynamic into a daily-life context, and the “expected of somebody” denotes an interpersonal, relational, or community context, the arena of sangha practice.

In Zen, we can maintain a personal aspiration, without having it devolve or deteriorate into an expectation. This is a fine line. If the kind of aspiration we bring to the cushion is to achieve something, it is already a kind of expectation. If, however, we can practice without expectation, we can still hold an aspiration. Aspiration to what, then becomes the question.

That we cannot clearly define or know, a priori, what it is that may be achieved in Zen practice – we can have no preconception of awakening — amounts to a kind of koan, an illogical puzzle or riddle. To sit in zazen without expectation, without even an aspiration to achieve something, seems counterintuitive, not based on the reality of everyday frustrations and failings we experience in our desire to mitigate suffering, both of ourselves and others.

We should understand that the instructions and admonitions given by our Zen Ancestors, e.g. Master Dogen’s kindly encouragement to “set aside all everyday concerns, think of neither good nor evil, right or wrong” (Fukanzaznegi) are meant to apply to time on the cushion. As soon as we rise and re-enter daily life, we are instantly and repeatedly confronted with unavoidable issues of good and evil, right and wrong, in the conduct of our daily dealings with others, from friends and neighbors to the government.

So our first level of expectations to be addressed consists of those that come on the cushion, expectations of direct results from meditation. The second level is that of indirect results, such as changes in our ability to cope with daily life situations; and perhaps a third is what we expect of the sangha itself, the members and leadership of the Zen center, and by extension our larger community of family, friends, colleagues and fellow citizens.

Narrowing the focus to the cushion, we naturally expect something to happen each time we sit. We hope to progress — for the zazen to become more comfortable, our monkey mind to settle down — and for the overall experience to be a positive one. Often this expectation is disappointed, as we confront resistance and pain on a physical, mental and emotional level.

It is actually considered beneficial to run into resistance in zazen, as it gives us something to work against, some sense of progress when the difficulty abates. We derive some satisfaction and encouragement from this sense that zazen is changing. Now we are getting somewhere, when we finally become comfortable in zazen. If zazen is too easy right away, it is not challenging, and we can slip into complacency. This is a bigger barrier than discomfort.

But the subtler dimensions of expectation versus aspiration while on the cushion are more difficult to nail down. They have to do with the skandha of so-called “mental formations,” which is itself a slippery subject. This has to do with the impulses underlying actions, including the impulse to practice.

For clarification on this more subtle realm of motive and desire, we turn to Master Dogen’s poem, Zazenshin; Needle for Zazen (S. Okumura trans.):

The essential-function of buddhas and the functioning-essence of ancestors

Being actualized within not-thinking being manifested within non-interacting

Being actualized within not-thinking the actualization is by nature intimate

Being manifested within non-interacting the manifestation is itself verification

The actualization that is by nature intimate never has defilement

The manifestation that is by nature verification never has distinction between

Absolute and Relative

The Intimacy without defilement is dropping off without relying on anything

Verification beyond distinction between absolute and relative

is making effort without aiming at it

The water is clear to the earth a fish is swimming like a fish

The sky is vast and extends to the heavens a bird is flying like a bird

This is a marvelously focused teaching, like the sharp needle used for acupuncture. It goes straight to the point, unfolding further with each stanza the phrasing from the former stanza, until the last, where Dogen brings us back to the concrete world in a poetic image of fish and bird. It is deserving of your study and memorization; it is often used in liturgy.

The fourth stanza gets to the point of aspiration versus expectation. Intimacy without defilement means, as Matsuoka-roshi said, “Your enlightenment is yours and mine is mine; you can’t get mine and I can’t get yours.” This is intimacy. Without defilement means there is no trace of something that can be reduced to conventional understanding, let alone advance expectation.

Verification beyond absolute and relative means that while this is a sure thing, and you can be confident of its veracity, it is outside the conceptual frameworks of the discriminating mind, language, and normal perception. But if we long for awakening, we miss the fact of our present enlightenment by substituting a conceptual expectation. That it is “making effort without aiming at it” indicates the ultimate aspiration, with no need for expectation. Loosing the arrow with no target in mind; arrow points meeting in midair.

Off the cushion, when we venture into expectations of others, especially in the context of the sangha, we get into trouble. Unless we are able to practice effort without aiming at it on the cushion, we cannot come to an appreciation of and integration with sangha. Our expectations will get in the way of the reality.

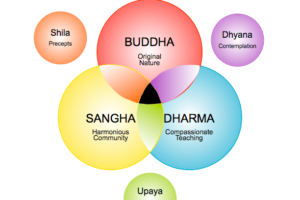

This is where the Precepts come into play, particularly those of not discussing the faults of others, and of not praising oneself at the expense of others. These are very subtle guidelines, easy to cross unintentionally, even if only in our own mind. If we expect too much of others, based on our preconceptions of Zen compassion, humility, wisdom, et cetera, we are bound to be disappointed. If, on the other hand, we expect too little, we demean the Treasure of the sangha.

The Middle Way indicates the course correction we can apply on the run, observing the behavior of others as well as our own. In Zen, we have the good fortune not only of a precious human birth, but of exposure to the Three Treasures and the joy of being able to return to the cushion for refuge. And to sit with the other members of the sangha by our side. Something happens — something is achieved — whether we are aware of it or not.

The extensive schedule of retreats and daily practice offered for 2011 is designed to optimize your opportunities to engage in this mindful practice of doing zazen alone on the cushion, while at the same time practicing with your dharma family in the zendo and the environment of the Zen center. Please take advantage of this unique opportunity to deepen your aspiration, and to jettison your expectations. Please commit to a regular schedule of weekly meditation, attending Zazenkai, and at least one major Sesshin this year. It is your roadmap to enlightenment, if not awakening.