SPECIAL MEMORIAL

We want to pay due respect to the passing of Rev. C. T. Vivian and Congressman John Lewis, two icons of the Civil Rights movement which found its origins here in Atlanta. They did their dead level best to “keep their eye on the prize” as Mr. Lewis would say. The prize was sometimes expressed as the “beloved community” with the lament that we are not yet there, here in the USA. The commensurate term in Buddhism is Sangha, the “harmonious community.” John Lewis and Rev. Vivian, like Jesus Christ, are considered to be Bodhisattvas, enlightening beings dedicated to others. Let us continue the struggle.

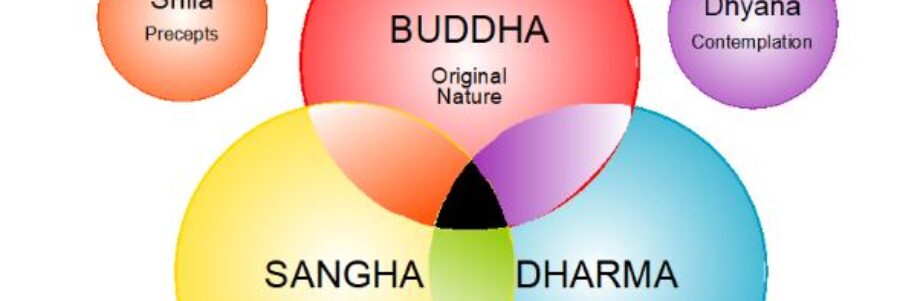

My interactive model of the Four Spheres of Zen—that is, those dimensions of reality that both impact upon, and are impacted by, the relationship of our practice to them, and their relationship to our practice—illustrates that while there are only four such, they have six connections, which if viewed as two-directional vectors, result in twelve such one-way channels. This is the fundamental 2-way street, or Path, that all sentient beings tread.

(Note: R. Buckminster Fuller taught that a tetrahedron is the simplest model of a “system,” in that it has an inside, and an outside. No simpler geometry—e.g. a triangle— has that basic characteristic of any system. He also said that if you can accurately name the four main components, and thoroughly describe the six connections, you could be said to “understand” that particular system. Apply it to anything you like, to get the basic idea.)

Thus we can examine the personal sphere of our Zen practice—starting with zazen, of course—and consider how it effects our social sphere; and in turn, how the social sphere effects our personal practice. For example, your spouse and other family members, or your associates at work, may not practice Zen. If and when they discover that you do, being ignorant of the truth of Zen, as well as curious about it, may ask you some fairly awkward questions. Especially if they are religious themselves, and have concerns about the salvation of your soul, as sometimes happens. Conversely, you may find that your Zen meditation is enabling an evolution of your own feelings about it, and how much weight you give to their opinion about it. This kind of sticky situation can lead to strengthening your understanding of the place of Zen in your life, or conversely become a discouraging distraction, even resulting in a kind of “crisis of faith,” a personal, existential koan.

Try the exercise of going through each of the four points and their six connections, in the context of the particularities of your personal situation. In the Natural realm, for example, considerations such as diet, consumption and recycling come into play. In the Universal sphere, we find an asymmetrical relationship, where it, the Universe, may have an immense impact upon us and our practice—as in aging, sickness and death, for example—but we cannot return the favor to any meaningful degree. Much like some of our personal relationships. Let us now add the Three Treasures into the mix.

This new diagram shows a relationship of the Three Treasures of Buddhism to my four spheres of Zen, featured in prior Dharma Bytes. While we can envision a nesting set of surrounding spheres of influence, from the personal to the universal—all impinging upon our practice, our practice influencing them to greater or lesser degree—the transcendent nature of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha dimensions suggest a halo effect beyond the personal, extending to the social most immediately, but also with implications for the natural and even universal spheres. We do not have time or space to do justice to this larger picture, so we will focus on Sangha for the present. Sometimes it is not so harmonious.

WE’LL BE THERE FOR YOU

The call went out as usual for someone to cover our Wednesday Workshop, the forum in which we give basic zazen instructions for newcomers, and try to answer any questions they, as well as repeat attendees and regulars, may have. It is one of the most important programs we sponsor, in propagating Soto Zen practice within the American community.

I responded several times to the query asking for volunteers to cover, copying the distribution list, of which there are currently upwards of a dozen volunteers trained to lead the newcomers session. Keeping the list current is in itself a repeat task, as members often become unavailable. I repeated that I would dependably continue to cover 5th Wednesdays, which I use to offer formal training to others to observe my approach, which I learned from Matsuoka Roshi, and have refined appropriately, I like to think.

With the advent of the pandemic, our usual rotational structure of staffing this time slot has been somewhat disrupted, as we cannot simply show up at the Zen center at the appointed time, but have to have support for streaming live online from there, or from at home.

For the first time in my memory, the start time came and went, with no one at the helm.

This was not the end of the world, of course. Anyone who attempted to join online, and was disappointed, had the option of notifying us. And indeed, we had a couple of missed connections, to which I responded online, explaining the glitch, and inviting them to join next time. So no harm no foul. However, if we consistently drop the ball on staffing our announced schedule, whether in person or online, people will just as consistently drop out, and finally give up on us. In retail, the expression is “Three strikes and you’re out.” We need to be dependable, in order to dependably propagate the practice and teachings of Zen.

Giving specific instructions for zazen is, again, one of the most important and foundational planks in our platform of Zen propagation, based closely on Master Dogen’s approach in 13th Century Japan. We train disciple and priest candidates formally, as well as any willing members on an informal basis, in leading zazen sessions. And as guiding teacher, I have usually stepped in to cover in an emergency, as substitute of last resort.

But this time, as I saw repeated calls for someone to cover, I decided that I would not volunteer, and see what happened. In recent years, I have been gradually tamping down my tendency to step into the breach as these situations arise. I am getting older, and we have plenty of younger people who are ready, willing and able to engage in deeper Zen training. Since our incorporation in 1977, I have not missed a publicly scheduled program that was not covered by someone else. But a community cannot survive for long, if it depends too much on any one individual. That is the basic structure of a cult.

THE BELOVED COMMUNITY ONLINE

Since Covid-19 appeared, we have ramped up our online activities, like everyone else. I am personally currently on call for individual dharma dialogs, booked on Tuesday and Thursday mornings at 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 1 o’clock; Fridays at 8, 9 and 10; plus regular monthly evening conferences with many of our affiliates. I am also a regular panelist on an international world peace movement out of South Korea. So I am keeping busy and staying in touch with the larger community.

I find both, one-on-one and group dialogs, very rewarding, and my correspondents also apparently do. The Q&A sessions tend to bring out aspects of Zen that would not likely emerge, absent the interactive dialog. We typically record them for future archiving, posting or publication. These are traditional aspects of Zen community: keeping contact, sharing dharma, and maintaining some record of the dialog. “We teach each other Buddhism,” as Matsuoka Roshi would often say.

WORLDWIDE SANGHA

“Mokurai” is the title of the collection of Sensei’s later talks from the 1980s, available online on our websites. It translates variously as “silence is thunder” or “stillness in motion; motion in stillness”—the resolution of opposites in non-duality. Two talks published therein are both titled “Zen Can Bridge East and West.” In the first, given at the dedication ceremony for a new Zen center community, he declares:

A Zen temple is many things to all people. It is, first of all, a place of quiet meditation and tranquility; it is also a gathering place for those persons of searching minds and deep spirits. It is a sanctuary from the noise and pace of the modern world and it is a place of learning ancient knowledge. It is, above all, a place of Enlightenment.

So the primary function of a Zen community (Sangha) today, whether located in the western or eastern hemisphere, is to provide some sanctuary from the madding crowd and maddening pace of so-called civilization, in order to do the hard work of waking up, with as little disruption as we can manage. To the degree possible, we strive to make the Zen center and meditation hall (zendo) a refuge from distraction and anxiety. We are careful to maintain a clean and quiet environment, and we inculcate sensitivity in all members to our central focus of supporting the individual in their meditation. We as individuals come to dedicate our practice to supporting that of others, turning our attention from our own concerns to the needs of the group. Sensei touches on this dual track of dedication, on personal as well as social levels:

Dedication is the key word today. We are dedicating a new Zen Center, but more than that, we must be dedicating ourselves. A Zen Center is empty in spirit if those who attend it are not devoted to Zen and diligent in practicing Zen meditation. Devotion and dedication to a life of Zen must be sincere and deep, a part of each living moment.

So dedicating a place, a building, grounds, the temple layout and meditation hall, is the same as dedicating ourselves. The facility without the Sangha is just an empty building. There is no separation of the individual and the environment, in Zen, just as there is no separation of subject and object. Your immediate surround is not separate from—in fact is—your mind.

In Zen, there is also no actual separation of the personal and the social, though the personal dimension of direct experience in meditation naturally comes first in priority of practice. Each of the Three Treasures of Buddhism—Buddha, Dharma and Sangha—has at least two sides, like this, the personal and the social. All three overlap and engage the four spheres of our world, including the natural and universal (see illustration above). Here represented as just touching tangentially, in reality they overlap like a Venn diagram (see illustration below).

THREE TREASURE = THREE PILLARS OF ZEN

The Three Jewels or Treasures of Zen represent our highest values, both on a personal aspiration basis and as a social paradigm. Buddha points to our “original nature,” that is our buddha-nature, which simply means our potential to be fully awakened. But it also indicates the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, and the ramifications of his establishing the original Buddhist Order some 2500 years ago, a community of committed mendicant monks and nuns. This was his contribution to the societal arena. There may have been many other experimental communities at the time in India, as we have also seen throughout the history of America. But the Sangha did not take on the established order head-to-head. It was meant to be an alternative way of life.

Dharma is often translated as “compassionate teaching” and includes the record of spoken teachings as recorded and handed down to successive generations since the time of Buddha, but also points at the truth as manifested in our daily lives. The written record represents a social sharing of dharma assets derived from the intensely personal experience of the Ancestors, while dharma as reality indicates our personal grasp of the deeper meaning of the Dharma in our lives, also derived from our personal experience in meditation, but with a halo effect on our relationships with others.

Sangha indicates and prescribes a “harmonious community,” and generally speaking, as long as we provide and preserve the sanctuary in which people can peacefully pursue meditation, we are doing the most we can do to preserve harmony in the community. A Zen sangha then becomes a microcosm of society at large. The same kind of boundary we experience between our personal sphere of influence and practice with that of others in our Sangha, is true also of the sphere of the Sangha interfacing with that of the larger community, which may not be so harmonious.

The overlapping zones may be regarded as engaging certain of the Six Paramitas, or perfections of Buddhism: Precepts as the ethical or behavioral bridge between Buddha and Sangha; the practice of Contemplation or meditation to comprehend the relationship of our own buddha nature to Dharma, Buddha’s teaching; and applying Skillful Means in the presentation of buddhadharma to the Sangha, and outreach to the broader community.

The nature of the relationship of Sangha to the societal reality may be seen in the formation of the 501c3 NFP corporation that defines the legal entity of the Zen center. Its only reason for being is that as a corporation, the Sangha can exist in harmony with other corporate entities, namely the state and federal governments and their agencies, including the IRS. Economic nourishment of the Zen center is supported by its ability to accept tax-deductible donations. But the entity does not consist merely in its legal form on paper, but in the living presence of its membership in real life.

Like any organic entity, the parts and pieces (members) of the Zen community continually come and go. We regard its dynamic as similar to that of a cloud (J. un), continually condensing and evaporating, shape-shifting. Members may be present for some time, over years or even decades. Others may be short-termers who arise and disappear in a few weeks or months. In light of this reality, we have adopted the motto first posted by Master Sokei-an, a Rinzai teacher contemporary with Matsuoka Roshi’s advent in America, which declares: “Those who come here are welcome; those who leave are not pursued.” The wisdom of this attitude has proven itself time and again, since the incorporation of ASZC.

We have come to define the ASZC community as a creative collaborative, a harmonious balance of the individual with the group. More like a jazz band than a classical orchestra. Jazz musicians have to be very humble and sharing; no one voice can dominate the performance if it is to be harmonic in every sense of the word. And they are called upon to improvise. There may be a chart to follow, staying within the chord progression, but the individual notes are up to the player’s imagination.

The collaborative community is open to all to join, but we do not attempt to decide how each member should participate, or what role anyone should play, other than diligently practicing Zen meditation, and supporting the practice of others to the best of their ability. A productive creative collaboration is usually between two people, who bring different skill sets to the same process. When we introduce a third, or fourth, politics often follow.

So we ask each member to focus on their own development in zazen, and in due time consider how and what they may choose to engage on the social level, functioning within, and in collaboration with, other members of the community. Some join the Board of Directors, others take care of flowers or replenishment of supplies, others lend their expertise online. When there is an obvious lack in our program or administration, someone will usually step up and step in. But nothing lasts forever, and the needs of the organization itself evolve over time. So the management of the community is an ever-changing challenge, a work-in-progress, a real Zen koan-in-motion.

In living and working with this illogical riddle of group practice, we encounter a higher, or at least a different, level of friction & frustration. If we recognize that this, too, is Dharma, then we are in a good position to learn from the process, and to mature in our practice. One of our current board members recently suggested that the administrative side versus the personal practice side are akin to the left- and right-brain functions of the mind. I think this an apt metaphor. I also feel that service to the community, especially on the administrative side of things, may be the highest level of contribution in that it can seem so un-Zen-like at times. But like a cloud—un—if we remember that the current Sangha is as diaphanous, and as precious, as the shade and rain from a cloud in the sky on a hot summer day, we can embrace any and all dimensions of Zen, from the trivial to the transcendental.

Please continue to support your Sangha in these challenging times. They are your extended Dharma family.