DharmaByteJAN2021

ZEN AS PROBLEM-SOLVING

Zen as a problem-solving activity means, among other things, that zazen represents a personal method for applying creativity to all dimensions of daily life, taken as problems looking for solutions. My background in design training places my approach to Zen at the intersection of Zen & design-thinking. In design training, we learn that problem solving begins with, and its success depends upon, problem definition: If you cannot define the problem, chances are not good that you can solve it. The theory goes that the fullest definition of any problem, if complete enough, will indicate the solution, or multiple solutions. Sometimes, of course, the problem definition phase redefines the problem as initially conceived. So it is with Zen.

It is also a truism in Zen and design that you have to fail in order to succeed. Master Dogen’s expression, “Fall down seven times, get up eight” is a concise and cogent as any I have seen from design sources. In my case, I make mistakes all the time, as a necessary part of the process. In science, they are called experiments, and there is no such thing as a failed experiment. The so-called failure yields the necessary data to readjust the experiment. In art and design, similarly you have to be ready to waste some paper in learning how to draw. The object is not to produce and object, a drawing, but to train yourself in the process, which is training the eye to see, and the hand to translate, what you are seeing, whether in your mind or in reality.

LANGUAGE AS PART OF THE PROBLEM

There ought to be a Precept prohibiting imprecision of language, a pet peeve of one of my mentors, R. Buckminster Fuller, which I quote in my soon-to-be-released first book — “The Original Frontier,” in the section on “Deconstructing Your Senses in the Most Natural Way” — in which I stress the principle that Zen teaching is beyond words, and so learning it must be approached directly, primarily through the senses:

Many of you think of yourselves as scientists, and yet you go off on a picnic with your family, and you see a beautiful sunset, and you actually see the sun setting, going down. You’ve had four hundred years to adjust your senses since you learned from Copernicus and Galileo that the earth wasn’t standing still with the sun going around it. …But you scientists still see the sun setting. And you talk about things being “up” or “down” in space, when what you really mean is out and in in respect to the earth’s surface.

Similarly, Zen training is about learning to experience our world based on reality, rather than preconception and received wisdom. Likewise, expressing Zen’s truth about our reality is hampered by our dependence on words and language in general, both to think and to express our thoughts. Zen, the arts and sciences, and design, all stress mental and emotional processes that are beyond words and language, thinking in images, sounds, movement, et cetera. Poetry is an example of using the medium of words to express the inexpressible beyond words.

THE FOUR SPHERES AND THREE TIMES To establish context for what follows I would like to refer to my model of the four concentric spheres that are contingent upon our practice — the personal, social, natural and universal realms — and remind us of the Three Times of Buddhism — past, future, and present — in which we find ourselves. This unique location in spacetime, to use Einstein’s unified expression, is the central axis of our personal sphere, as well as the standpoint from which we regard all the others. Needless to say, the outer spheres exert a greater influence on the inner, personal sphere, in general, than we can influence upon them. This is the beginning of humility.

UNIVERSAL

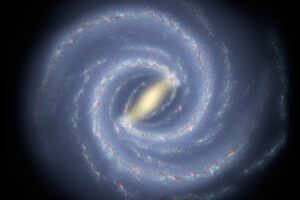

In contemplating the universal, we find that words fail, and we have to rely on something that goes beyond language, the ability to visualize ideas, or imagination. This power of the mind might be considered a form of non- or un-thinking, “seeing” in the deeper senser of the word, or “Imagineering,” a term coined by the legacy of Walt Disney, an earlier mentor in my visually-biased worldview. Think of this as an exercise in using your internal visual aids. I would ask you to picture this:

A SciFi-like 4D Image (holographic) in space & time (Spacetime), floating in a sphere (ok a cube, if you are terminally Cartesian) about 3’ on all axes (3 if Cartesian, 6 if Geodesic, 10 if Buddhist). Now I want you to visualize the Milky Way Galaxy, floating in scale with your imaginary chamber, rotating there in its spiral serenity. Then zoom in on one of the four radial arms (called the Orion arm) at about 27,000 light years from the galactic center (the diameter being a bit over 100,000, so roughly halfway between the center and the outer edge, if you must know). There you will find our home Solar System, with its identified 8 or 9 planets (depending on where you land in the Pluto debate), and zooming in on the sun, our humble home planet Earth, with its lovely satellite, the Moon. Zooming further in, move to the Northern Hemisphere, the Western Hemisphere side of it, and you find the North America continent, home to the United States. Zooming in further, we enter the Easter Standard time zone (or that where you currently reside), then the Great State of Georgia, with that cluster of light called Atlanta, and on in to your home address and you sitting there in zazen.

Now imagine a blinking red light, say on the crown of your head, blinking once an hour, say, which locates the specific intersection of longitude and latitude, the 90-degree cartesian grid appliqued onto the globe, where you find yourself in spacetime.

Leaving the blinking light there as your marker, now run the zoom backward, taking into consideration the following: the rotation of the earth at roughly 1,000 miles per hour toward the “east”; the elliptical orbit of the planet (averaging a bit under 93 million miles radius from the sun — the so-called “astronomical unit,” or AU) seen as “counter-clockwise” if viewed from “above” the plane circling the sun, “clockwise” if from down under (see: Australia).

Setting aside for now such minor details as the nutation of the earth around its axis, which contributes to seasonal change, along with the changing distance from the sun; the acceleration and slowing of the earth at certain points in its orbit; and the relatively negligible influence of the moon in sub-orbit, which adds tidal pull to the dynamic. Now exit the solar system, which if measured by Pluto’s orbit, is about 7 and a half billion miles in diameter, or 80 AUs, 80 times the distance of the third rock from the sun.

Add one further arc to the narrative, that of the solar system itself orbiting the galactic center (which from Atlanta would be looking to the “south” in the sky, relative to which the earth, moon, old sol and the other planets are moving in an “upward” trajectory). The galaxy rotates at about 468,000 miles per hour, which estimates say will complete a galactic orbit in somewhere between 225 to 250 million terrestrial “years.”

If you have been able to keep in mind this image of the flashing red light as you transit through this whirligig rollercoaster of movement you would see it speed up in frequency, becoming constant, and that you are nowhere near where you thought you were from hour to hour, day to day, or year to year, as you move away into ever-larger scales of spacetime. Your little light is tracking a dizzying spiral through the solar system and the galaxy, in which the very idea of an hour or a day or a year in time, is lost in the shuffle.

This kind of dilation and compression in space and time, from distant to proximate causes and conditions, from past to present — embracing the universal within the intimate — is not alien to Zen, and not inaccessible to our immediate perception. An example from my former life as a globe-hopping traveler: When you take off in an airplane near the ocean or any large body of water, at first the waves on the surface seem to be moving by in a rapid flow. But if you keep your eyes on the water, as the airplane rises rapidly to greater heights, the surface of the water seems to become more and more calm, the waves smaller and smaller, until from cruising altitude it looks absolutely still. Master Dogen notes this perceptual phenomenon in his “Genjokoan” fascicle:

When you ride in a boat and watch the shore you might suppose that the shore is moving but when you keep your eyes closely on the boat you can see that the boat moves.

Similarly when you examine the myriad things with a confused body and mind you might suppose that you mind and nature are permanent but when you practice intimately and return to where you are it will be clear that nothing at all has unchanging self.

Typical Dogen – just when you get comfortable agreeing with his astute observation, it takes an ugly turn. All of a sudden you and your pesky delusions are the focus of his attention. Then he launches into his analogy from nature of firewood and ash, which he also makes personal. This brings us to the natural realm, or sphere.

TO BE CONTINUED

Now that we have reached cliffhanger status, we will continue this exploration of the existence and/or non-existence of the old year and New Year meme next month, when we will examine the Natural, the Social, and the Personal dimensions of the notion.